About Me

- Name: Estee Klar-Wolfond

- Location: Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Writer/Curator/Founder of The Autism Acceptance Project. Contributing Author to Between Interruptions: Thirty Women Tell the Truth About Motherhood, and Concepts of Normality by Wendy Lawson, and soon to be published Gravity Pulls You In. Writing my own book. Lecturer on autism and the media and parenting. Current graduate student Critical Disability Studies and most importantly, mother of Adam -- a new and emerging writer.

- Adam Wolfond's Blog

- MIT Presentation: From Fear and Fascination to Respect: A Fair Way of Referencing Autism in Science and Society

- The Belonging Initiative

- The Disability History Museum

- Disability Nation Online

- Disability Studies, Temple U

- Dr. Flea

- Patricia E. Bauer

- Parenting a Complex Child

- Planet of the Blind

- Ragged Edge Online

- Reports on Autistic Abuse

-

"Only that thing is free which exists by the necessities of its own nature, and is determined in its actions by itself alone.” -- Spinoza

- Abnormal Diversity

- Aspies For Freedom

- Asperger's Conversations

- Asperger Square 8

- Aspieland.com

- Auties.org

- Autism Assembly

- Autistic Advocacy

- Autism Crisis

- Autism Diva

- Ballastexistenz

- Elmindreda's Blog

- Kindtree.org

- Laurentius Rex

- Homo Autistic

- Evidence of Venom

- Michelle Dawson

- Michael Moon

- Neurodiversity.com

- Part Processing

- Pre-RainMan Autism

- Square Girl

- Whose Planet Is It Anyway?

- Estee in The Toronto Star

- Estee Re:Jonathan Lerman on Canada AM

- Global TV Clip Jonathan Lerman and Autism

- Gallery Statement Re:Jonathan Lerman

- Bloorview MacMillan "Adam in the Snoezelen Room"

- Toronto Life Magazine

- Art and the Autisic Mind

- Autistics.Org

- Google Autism News

- Kaplan Learning Materials

- Laureate Computer Products

- Learning Materials

- Lonsdale Gallery

- Ministry of Ontario School Curriculum

- MukiBaum Treatment Centres

- Philosophical Dilemma of Autism

- Project Ability (UK)

- Software and Hardware for Autism

- The Infinite Mind Special Report on Aspergers

- Three Reasons Not to Believe in an Autism Epidemic

- Respectful Insolence

- Autism Voice

- Action for Autism

- Adventures in Autism

- Along The Spectrum

- Autism Natural Variation

- Autism Street

- Autistic Conjecture of the Day

- Autism Mom Speaks Out

- Autism Edges

- A Touch of Alyricism

- Day Sixty Seven

- Hazardous Pastimes

- In The Trenches

- Keven Leitch

- Lisa-Jedi

- Martian Martian

- Memory Leaves

- Mom To Mr. Handsome

- More Than A Label

- My Autistic Boy

- My2Sons

- Mom Embracing Autism

- Mom - Not Otherwise Specified

- Susan Senator

- This Mom

- 29 Marbles

Tuesday, August 29, 2006

Monday, August 28, 2006

The Perils of Representation and Communication

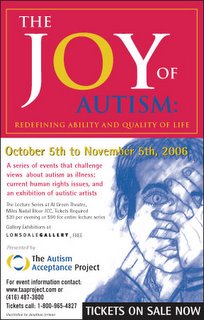

The exhibition of autistic artists at The Lonsdale Gallery in Toronto as part of The Autism Acceptance Project will begin in a month. The exhibition serves many purposes:

1. To demystify many myths about autism, as art is communication and speaks for itself;

2. To celebrate autistic artists and people instead of instilling fear and doom;

Is this putting art on a pedestal thereby seeking to sensationalize autism? If we sensationalize autism, or the work of autistic artists in a spotlighted way, are we at risk of perpetuating another myth: autism and genius?

Last year, Jonathan Lerman was portrayed by certain media people as a “genius.” It bothered me on the one hand – Jonathan, this wonderful young man, understood and perhaps accepted by others only for his “genius.” While I was ecstatic that Jonathan was reviewed and revered, I felt that something was taken away from his personhood in the process. There are hazards in representing others, and communicating about autism. I recognize these perils and not only take responsibility for them, but also keep aspiring to communicate in a way that continues to achieve understanding and respect. Communication is an art – it is difficult for most of us at the best of times. However, with the divide as huge as it currently is, that is, between parents, society and autistic people, I consider the goal an important challenge.

Some people say discourse is a process. Others believe that acceptance is not a discourse. In my post The Learning Curve of Acceptance I said that acceptance is a process, as unfortunate as that is, and that as we learn about autism, listen to autistic people, our assimilation of knowledge about autism takes time, mostly because there is so much assumption and inaccurate information about autism. I think many of us have realized that acceptance doesn’t exist to the full extent that we need it to, and communicating about autism is ambiguous, paradoxical and difficult in the midst of the doom messages that are popular. The work of Michelle Dawson, Jim Sinclair, Amanda Baggs, Kathleen Seidel and others has been integral to intelligently understanding autism and the issues that abound when non-autistics begin discussing autistic people.

How we present the work of autistic artists is important as is discussing their work. Do we regard the work of autistic artists with awe because they are autistic, or do we regard the work for itself? When we consider the work in the latter context, we can then regard the person behind the work with respect. There seems to be some confusion in granting respect and equality to autistic people. Equality simply means that despite race, creed or disability we all deserve to be regarded equally while acknowledging challenges and differences.

The work involved in creating something is arduous. To believe that it comes just from some autistic stream of consciousness – that it just flows because of the autism -- is part true and untrue. There is always the work, the hours spent creating and perfecting it. I consider the hours that Jonathan spends at his art studio and the hundreds of paintings awaiting my attention at Larry’s. Their work is prolific. Jonathan’s work appears lucid, full of emotion. Larry’s, on the surface, looks more like folk art. What makes Larry’s work fascinating and important are the titles he ascribes his work, as important as the work itself and as inseparable as Siamese twins. His titles read like metaphors, poems. I am in awe of his use of language that rings with profound meaning. While the way in which he writes may come in part from autism, it is also indigenous to Larry. He has the ability to describe the world like a poet who can pinpoint the complexity of truth in a mere phrase.

In this respect, Larry and Jonathan have worked to SEE. Seeing, observing, understanding, assimilating in a way that touches us in a mere moment – the toilsome work of perceiving and understanding the world and manifesting that in a work of art, or literature, or poetry for that matter – this is a process that demands the artist to actively participate in the world.

Kamram Nazeer, an autistic policy advisor at Whitehall and writer, addresses our banal understanding of genius in his book Send in the Idiots. He notes that when we designate an autistic artist or writer a “genius,” we are taking away their dignity because we are in essence saying that there is no effort behind the work. When we believe this, we have once again diminished not only the work, but also the person behind it:

GENIUS:

“The term obscures; it provides an area of grace. The problem with the term `genius,’ however, is that we do not only use it for the purposes of bereavement. We use it commonly. And we use words and attitudes that are similar in effect.”

The work by autistic people deserves the “full and proper rigor to the life of the ordinary, though very clever, subject but not to the life of the genius…. If the task of criticism is to somehow explain, or make guesses, or lead interesting speculations as to how works come to be or how they do what they do, the use of the term `genius’ must be eschewed. It reveals nothing, it gives no insight into the creative process; by using it, we get no further.”

Genius has to work hard too. Our conception of privileges of genius is a false one.

Genius has to engage with tradition.

Perhaps the greatest achievement and finest use of the term `genius’ is that it makes us feel safe. By using it to identify a group of individuals who are different from us, and we refuse to engage with how it is that these individuals do what they do. We accept that their achievements do not depend on anything but the special quality of genius itself.

Genius doesn’t rely on us.

Genius just is. Hence, the overall effect is that we completely rid ourselves of any responsibility for progress. We don’t have to understand what they do. We don’t have to aspire to do it ourselves. In return, we give geniuses certain special privileges. We cannot hold them to ordinary standards of behavior, for example. And in the end, we are able to remove ourselves from the great game. This is incredibly liberating. We can now enjoy our private lives. We need never feel anxious about our “contribution.” (excerpts from pages 79-88)

Genius is creative activity with hard work. It is true for all of us. Are these works of genius at The Lonsdale Gallery? Maybe yes for some, and no for others. But let us not put these artists on pedestals because of their autism. Let us regard the work for itself, and then we can also come to understand the person behind the work. If art is also communication, let us actively seek out what it is trying to communicate. Art, like all communication, is a two-way process.

The TAAProject video which will be released this week, is set to celebrate autistic people and to provide a positive view among society-at-large so that we can begin shifting paradigms. It is not perfect. I consider the video a work in progress, reflecting how views are in the midst of changing. It is a beginning for the general public to have access to something different about autism. The next video will begin to address the complexity of our beliefs about autism, even those beliefs that suggest that autism is a special ability. It is and isn’t any of this. Autism just is.

How do we explain autism to the general public, if not one step at a time? This is our very first step. I believe it is for the better.

1. To demystify many myths about autism, as art is communication and speaks for itself;

2. To celebrate autistic artists and people instead of instilling fear and doom;

Is this putting art on a pedestal thereby seeking to sensationalize autism? If we sensationalize autism, or the work of autistic artists in a spotlighted way, are we at risk of perpetuating another myth: autism and genius?

Last year, Jonathan Lerman was portrayed by certain media people as a “genius.” It bothered me on the one hand – Jonathan, this wonderful young man, understood and perhaps accepted by others only for his “genius.” While I was ecstatic that Jonathan was reviewed and revered, I felt that something was taken away from his personhood in the process. There are hazards in representing others, and communicating about autism. I recognize these perils and not only take responsibility for them, but also keep aspiring to communicate in a way that continues to achieve understanding and respect. Communication is an art – it is difficult for most of us at the best of times. However, with the divide as huge as it currently is, that is, between parents, society and autistic people, I consider the goal an important challenge.

Some people say discourse is a process. Others believe that acceptance is not a discourse. In my post The Learning Curve of Acceptance I said that acceptance is a process, as unfortunate as that is, and that as we learn about autism, listen to autistic people, our assimilation of knowledge about autism takes time, mostly because there is so much assumption and inaccurate information about autism. I think many of us have realized that acceptance doesn’t exist to the full extent that we need it to, and communicating about autism is ambiguous, paradoxical and difficult in the midst of the doom messages that are popular. The work of Michelle Dawson, Jim Sinclair, Amanda Baggs, Kathleen Seidel and others has been integral to intelligently understanding autism and the issues that abound when non-autistics begin discussing autistic people.

How we present the work of autistic artists is important as is discussing their work. Do we regard the work of autistic artists with awe because they are autistic, or do we regard the work for itself? When we consider the work in the latter context, we can then regard the person behind the work with respect. There seems to be some confusion in granting respect and equality to autistic people. Equality simply means that despite race, creed or disability we all deserve to be regarded equally while acknowledging challenges and differences.

The work involved in creating something is arduous. To believe that it comes just from some autistic stream of consciousness – that it just flows because of the autism -- is part true and untrue. There is always the work, the hours spent creating and perfecting it. I consider the hours that Jonathan spends at his art studio and the hundreds of paintings awaiting my attention at Larry’s. Their work is prolific. Jonathan’s work appears lucid, full of emotion. Larry’s, on the surface, looks more like folk art. What makes Larry’s work fascinating and important are the titles he ascribes his work, as important as the work itself and as inseparable as Siamese twins. His titles read like metaphors, poems. I am in awe of his use of language that rings with profound meaning. While the way in which he writes may come in part from autism, it is also indigenous to Larry. He has the ability to describe the world like a poet who can pinpoint the complexity of truth in a mere phrase.

In this respect, Larry and Jonathan have worked to SEE. Seeing, observing, understanding, assimilating in a way that touches us in a mere moment – the toilsome work of perceiving and understanding the world and manifesting that in a work of art, or literature, or poetry for that matter – this is a process that demands the artist to actively participate in the world.

Kamram Nazeer, an autistic policy advisor at Whitehall and writer, addresses our banal understanding of genius in his book Send in the Idiots. He notes that when we designate an autistic artist or writer a “genius,” we are taking away their dignity because we are in essence saying that there is no effort behind the work. When we believe this, we have once again diminished not only the work, but also the person behind it:

GENIUS:

“The term obscures; it provides an area of grace. The problem with the term `genius,’ however, is that we do not only use it for the purposes of bereavement. We use it commonly. And we use words and attitudes that are similar in effect.”

The work by autistic people deserves the “full and proper rigor to the life of the ordinary, though very clever, subject but not to the life of the genius…. If the task of criticism is to somehow explain, or make guesses, or lead interesting speculations as to how works come to be or how they do what they do, the use of the term `genius’ must be eschewed. It reveals nothing, it gives no insight into the creative process; by using it, we get no further.”

Genius has to work hard too. Our conception of privileges of genius is a false one.

Genius has to engage with tradition.

Perhaps the greatest achievement and finest use of the term `genius’ is that it makes us feel safe. By using it to identify a group of individuals who are different from us, and we refuse to engage with how it is that these individuals do what they do. We accept that their achievements do not depend on anything but the special quality of genius itself.

Genius doesn’t rely on us.

Genius just is. Hence, the overall effect is that we completely rid ourselves of any responsibility for progress. We don’t have to understand what they do. We don’t have to aspire to do it ourselves. In return, we give geniuses certain special privileges. We cannot hold them to ordinary standards of behavior, for example. And in the end, we are able to remove ourselves from the great game. This is incredibly liberating. We can now enjoy our private lives. We need never feel anxious about our “contribution.” (excerpts from pages 79-88)

Genius is creative activity with hard work. It is true for all of us. Are these works of genius at The Lonsdale Gallery? Maybe yes for some, and no for others. But let us not put these artists on pedestals because of their autism. Let us regard the work for itself, and then we can also come to understand the person behind the work. If art is also communication, let us actively seek out what it is trying to communicate. Art, like all communication, is a two-way process.

The TAAProject video which will be released this week, is set to celebrate autistic people and to provide a positive view among society-at-large so that we can begin shifting paradigms. It is not perfect. I consider the video a work in progress, reflecting how views are in the midst of changing. It is a beginning for the general public to have access to something different about autism. The next video will begin to address the complexity of our beliefs about autism, even those beliefs that suggest that autism is a special ability. It is and isn’t any of this. Autism just is.

How do we explain autism to the general public, if not one step at a time? This is our very first step. I believe it is for the better.

Friday, August 18, 2006

Autism Podcast

Thanks so much to Autism Diva and Autism Podcast for this wonderful show. I hope all of our Toronto readers will listen:

click on this: Autism Podcast

I am in Haliburton, sitting in an Internet Cafe while listening to this. Across from me sits "The Rails End Gallery" with a sign that reads: ART IS TRIUMPH OVER CHAOS.

The autistic artists who will be exhibited certainly are triumphant, showing an ability to take the abstract and make it into an interpreted, cohesive whole. Hopefully, with every word and deed, the same can occur for views about autism. Thanks again, Diva!

click on this: Autism Podcast

I am in Haliburton, sitting in an Internet Cafe while listening to this. Across from me sits "The Rails End Gallery" with a sign that reads: ART IS TRIUMPH OVER CHAOS.

The autistic artists who will be exhibited certainly are triumphant, showing an ability to take the abstract and make it into an interpreted, cohesive whole. Hopefully, with every word and deed, the same can occur for views about autism. Thanks again, Diva!

Wednesday, August 16, 2006

The Pill to Cure The Autism Divide

I’ve received positive and negative responses to The Autism Acceptance Project’s title “The Joy of Autism.” As expected, not everyone sees the joy in autism, at least not immediately. Many find autism a challenge and the joy of autism, elusive.

Yet, there is a tie that binds all parents, those of us who want services, education, and opportunities for our children. There is little difference between the devotion many of us feel towards our children, the daily commitment toward them in ensuring their success.

The difference lies in our attitude towards our autistic children. Is success defined within the frame of “normal,” or is it defined individually, without preconceptions? The idea of normal baffles me. In trying to define normal, I only come up with more absurdities.

When we believe that something is extrinsic of us, then we can blame something outside of ourselves, our children. For some parents of autistic children, it might be easier, although there is no scientific evidence to prove this, to believe that autism is a mask that shields the true child within, or that autism is a disease akin to cancer, waiting for a cure. To acknowledge that autism is as much a part of the child as congenital blindness or deafness, may be akin to telling a parent that their autistic child is dead. To acknowledge autism as part of the child may seem hopeless, but this project is here to show others that it is not. The devastation a parent might feel in light of these ideas, that their child will “never” do something that was expected, can be crippling, and may even lead to hatred, some of which will be directed towards this project that wishes only to preserve the dignity and opportunity for not only our autistic children, but also for adults who are speaking up. These adults are saying “autism is part of who I am.”

As a parent who has gone through the very same experiences of other parents, who has seen the devastating messages and videos, I asked myself, “how is all of this going to help my son Adam or my family? How will this effect his self-esteem, and the challenges of being accepted into the mainstream community? Ralph Savarese, a professor from Grinnell College, who has written a memoir titled Reasonable People: A Memoir of Autism and Adoption, stated,

“As a father of an Autist, I can tell you that feeling good about oneself is a big problem with autism. What do you say to an eleven-year-old who so understands the world’s intolerance of difference when he starts announcing on his computer at night, `freak is ready for bed’? Like other people with disabilities, some with autism have found that identity politics offer a vehicle for fighting discrimination and improving self-esteem. It locates the problem with difference where it should be: outside the self, in a world of ignorance and fear.” (p.13)

In other words, placing judgment of others outside of ourselves, is an important way to preserve self-esteem. This is why The Joy of Autism event is hosting the work and presentations of autistic people.

Judgment was the first negative experience we faced when going through the diagnostic and early intervention process. There are people who judged Adam from the outset, peering at him as a pathology. They became more focused on what he couldn’t do rather than what he could do. I wouldn’t say those are good teachers. A good teacher is one who can see the child for who they are, to find a entry point, to teach where a child’s interest lies, to understand the challenges and address them without using them to define the child. One seasoned teacher told me last night, “I became a good teacher when I realized that the content of what I was teaching wasn’t important, it was the child who was important.” Read that sentence carefully and find the profound wisdom in it.

Michael Moon, who seems in many ways non autistic today on the exterior, claims that he was very challenged as a young autistic child, and continues to find challenges as an adult despite his higher functioning. As a teenager he suffered chronic fatigue syndrome from trying to “fit in,” not yet understanding that he was autistic. “When I found out I was autistic, it was a relief,” he said. “I knew I fit in somewhere.” He says that at the age of twenty, when he found out about his diagnosis, the world shifted, and he was more able to become part of it.

“School didn’t help me,” he said. “Schools were more interested in how you followed rules rather than teaching.”

Brian Henson, an Asperger’s adult from Brantford, Ontario also relays similar pain from his school years. “Teachers only wanted me to read the text book. I couldn’t ask questions. When I wanted to explore something, they told me to just read the text or I would get an F.”

“We’re only teaching your child how to respond,” said Jim Partington to me over the phone, a few days before I considered flying him to Toronto. Adam was only two years old. He was not relating to us well, and consistently ran back and forth. I thought, that teaching Adam to respond was not the means to an end. I wanted to teach him how to relate to me, and to be happy. We succeeded with lots of play. Adam is extremely intelligent, showing his knowledge in variant ways, one being the computer. He can do all of the skills suited to his age, and then some. He has more difficulty responding in a typical way. While we teach him now that he is older, happy and with respect for him (not using normalization of him as a goal – semantics are important here), I feel that we are building bridges between his world and ours.

When Adam was at camp, his head counselor asked his shadow, “what is it?” in terms of his limited speech, to which his shadow wisely replied, “he’s a child.” What difference would it have made for this young person to know that he was autistic? Would it have furthered her understanding of Adam as a whole child, or simply categorized him as an incapable one? I continue to ask the question: does the autism label help or hinder? If it serves to support autistic people and have them regarded as whole people as well, then I can support its use. If it is used to paint a horrific, disease-identity, where an autistic person is refused by teachers, therapists, and others, then it is wrong.

Paula Kluth, Ph.D., formerly from Syracuse University, and an expert in inclusive education and US legislation cites a quote by an autistic person:

“All my life I was enrolled in classes for the profoundly retarded. The pain of that isolation, I can’t describe. Some classes consisted of putting together flashlights together and then they would be taken apart for the next day’s project. I never spoke or made eye contact. I hummed and self-stimulated. No wonder they though I was hopeless. I was always treated well but my intellectual needs were never addressed because nobody knew I had any intellect at all. Sad to say, many like me remain in that same hellish situation.” (Kluth, You’re Going to Love this Kid: Teaching Students with Autism in the Classroom, p.23)

If there is any social injustice in the world that does a disservice to autistic children, it is those organizations and individuals who continue to paint autism as a horrible way of living and being. These are the same organizations that could help with what is: the reality that there are autistic people living in the world, who need education, and that there are families who need to feel inspired and empowered, not constantly pounded with the message that their child is insufficient. This is the disease mind-set that is negatively effecting so many people. If autistic people suffer, it is not from their autism. It is from society who judges them.

Jim Sinclair acknowledges the process of parental grief stating basically, that although it is understandable, it is not right to take one’s grief out on the child. He offers some advice, being an autistic person himself:

“After you’ve started letting go, come back and look at your autistic child again, and say to yourself: “This is not my child that I expected and planned for. This is an alien child who landed in my life by accident. I don’t know who this child is or what it will become. But I know it’s a child, stranded in an alien world, without parents of its own kind to care for it. It needs someone to care for it, to teach it, to interpret and to advocate for it. And because this alien child happened to drop into my life, that job is mine if I want it. If that prospect excites you, then come join us, in strength and determination, in hope and in joy. The adventure of a lifetime is ahead of you.” (from his essay, Don’t Mourn for Us)

I have to say that the turning point for me was when I began to read the books and essays written by autistic people and autistic artists who have found a language outside the written word: Lucy Blackthorn, Richard Attfield, Donna Williams, and so many others. Some of who can’t talk, and who have dealt with challenges, and society’s stigmatization of them for a lifetime. This stigma effects the entire disabled community, who despite their disability, want to be accepted and want the same things as you and I. The vast majority believe that disability means incapable. The idea that there is actually a sentient being behind the exterior of disability is intolerable to many, but precisely the opposite is true and must be dealt with head-on.

Over the past three years, and especially the past year, I have made an effort to travel to meet many autistic adults all over North America – some with “severe” autism, “Kanner’s Autism,” Asperger’s Syndrome. I have met adults who were mainstreamed into schools when schools didn’t know the word autism to the extent we do today. I have met others who were institutionalized in the 1950’s when it was considered shameful for families to have children with any disability. Some of these people, now adults in their late fifties and early sixties, said they were put on psychotic drugs and were treated poorly. One woman I met from just outside of Toronto was diagnosed with “Kanner’s Autism” has worked for thirty years since leaving a psychiatric hospital. As a child, she was placed in a facility for children with emotional disturbances. She managed to get married, drive, work and live her life as we all do.

Barbara Moran, from Topeka, Kansas (I am careful whose names I will use – I have received permission from some but not others as of yet), stated that she too was institutionalized. She says "just think of all children who were autistic placed in institutions back then, who we never hear from." Now in her fifties, she is extremely sensitive to noise and cannot work. She says she could have done better if she was accepted and allowed to go to regular school “where I could have been desensitized,” she notes. She says that the drugs she was placed on nullified her, and she hated being on them.

Larry Bissonnette, who uses a keyboard to communicate full sentences said to me “people who think your disability is an illness need to be cured of their ignorant attitudes.” Larry was also institutionalized until his sister saw how he was treated. She pulled him out and now lives with her, making art, traveling around the world on occasion. I met him and experienced his humour, his human-ness. Despite the challenges in communication, he is profoundly intelligent. It breaks my heart to receive emails from parents who cannot find the daily joy in their children, in these people who can teach us everything about autism.

Science has not yet provided any answers about autism, only more questions. Some science is unveiling the abilities innate to autism, thankfully, as it garners respect for a human condition, creating the needed bridge between so-called “different worlds,” to reveal that our worlds are not that far apart. As a parent who has sought answers from a variety of autistic adults, after hearing them tell me of their experiences, what worked for them and what didn’t, and the overriding message of each of them wanting to enjoy life, to be tolerated, understood and accepted by society, I had to ask myself what the point was in attempting to “normalize” Adam. For to do so would have meant that I did not value him as he was, or was unhappy with him.

No, autism is a challenge for the rest of us because we only see through one lens. We have to ask ourselves – is it the only lens? Is it the only way to look at autism? What of the autistic perspective? Is there a right way to be and a wrong way to be?

I’ve met parents who have revealed to me that “of all my children, my autistic child brings me the most joy.” This comes from two families I have encountered personally. Many others write about it: Paul Collins, Susan Senator, Valerie Paradiz, are some. It is something I strongly relate to, as Adam is my first and only child, my life, my reason for being, my utmost joy. Reframing my expectations of him has brought me daily surprises. I no longer expect myself in my pencil skirt and hat sitting at his Harvard graduation, but I also can’t say it won’t happen, or that I might not be sitting at his high-school graduation beaming at his success. As parents, we all know that the milestones our children do achieve give us monumental joy.

My husband likes to play devil’s advocate. I like that because I never think that there is one conclusion. Autism has revealed that to be human is living in paradox. He asks me, “So what if there was a pill to cure Adam? How are you gonna answer that?”

I can’t say that is an easy question to answer. Do I want Adam to suffer the stigmatization that a judgmental society will bring upon him? No, of course I don’t. I’m not sure if a pill could ever cure external judgment of him or of me for that matter.

Is autism curable? There isn’t one scientist that has proclaimed that it can be. In fact, the landscape of autism is so diverse, that one magic pill might not do the trick for everyone.

And if there was a pill? I just don’t know. To answer that question quickly is scarier than the question itself. Autistic people say that autism is a challenge, but still, they don’t want to be cured. Oliver Sacks once noted that we need to appreciate diversity in all its forms and called the brain “remarkable [in its] plasticity, its capacity for the most striking adaptations” as the “creative potential” of disease itself. People who have been medicated to the hilt, nullified of their experiences with neurobiological disorders, have suffered a marked decline of their creative abilities. I have to listen to this. We all do. If there was that pill, I would want Adam to decide, but even that answer is much too simple.

So do I deal with the reality of what is? Absolutely.

So now, I will reveal some of the responses, calling The Autism Acceptance Project “a political fringe,” to which I do not sigh, but perhaps acknowledge because eventually, a fringe becomes a mainstream. At least I hope that tolerance and acceptance will become mainstream. This project is about celebrating human dignity, potential and seeks to perpetuate respect so that we can ask for a variety of services and education to governments and teachers who just might see the individual potential of an autistic person. Waiting for a cure will not help us obtain services, support, vocational training. Governments will simply wait for those cures as a cost-saving measure.

Jonathan Lerman in Vestal, New York, is experiencing something akin to an team that enables his self-determination and empowerment, with support. It is a government-funded program. I cannot attest to how it is working, but the concept is interesting and might be considered. Jonathan basically states what he wants to do, and his team of people that support him, including his parents, ensure that his wishes and goals are realized. I believe that teenagers should continue to be supported with their peers, with self-image, that adults should receive vocational training, placement and support. I believe that inclusive education is a right, and that special education is also a right. Autistic people need access to a variety of approaches and educational opportunities. Above all, autistic people need self-determination.

How do the following statements encourage or hinder these needed services? To paint autism as a horrific disease waiting for a cure? Or an ability, a way of being, that deserves respect and opportunity to reach its potential? I am not revealing these responses out of disrespect for those who wrote them, or to create more divisions, but rather, as an opportunity for us to see the difference between empowerment/disempowerment in hopes that some may choose to find the same kind of joy and inspiration that my son has brought to our family.

Response #1:

I have to say; shocked is a mild word for my reaction.

As a parent of a child with autism, I applaud any effort to help the world understand this mysterious condition and the enormous strain it puts on those it afflicts and their families. However, to de-stigmatize autism with a sugar coating does this challenge a major disservice. Many of us actively advocate for those suffering with autism and accurate public education is critical. Making autism seem like “a happy place” doesn’t help our cause.

Response #2

While I am sure we all appreciate the benefits that accrue to children who are involved in artistic self-expression (and I am particularly sympathetic to this as a professional musician), this is an issue quite separate from the matter in hand - which is the choice of or tacit approval of the title "The Joy of Autism". This will not produce controversy, it will elicit fury. Parents who are trying to access funds and services, who are managing children with trying behaviours and who are fighting for educational equality do not want to have to deal with its implications.

What is next? Happy and Leukemic? Cancer is Cool? Incest is just another kind of love? I really hope you will not only appreciate the full horror of this gaffe, but do something public to acknowledge it! The good the event is certain to achieve will doubtless be diluted by the negative reaction from the autism community.

Response #3 (I apologize for the awkward spacing as this was taken from an email to me from Kevin Leitch of Autism Hub):

As parent to an autistic child considered to be 'classically' autistic

(other terminology includes low functioning/Kanners) one of the most

troubling aspects of the international autism community (by which I

mean the self appointed organizations of largely non-autistic people)

as oppose to the autistic community (by which I mean the organizations

comprised of a mixture of autistic and non-autistic people, or solely

autistic people) is the way in which a lot of people are opposed to

any attempt to present a non-tragic face to autism.

There is no denial that raising a child who has special needs is

difficult but it worries me that people want to compare an attempt to

look at a less negative aspect of autism to incest and cancer.

It seems to me that there is a large element of pre-judging occurring

here. Both in terms of what the event itself is and in terms of what

autism 'must be' for all people.

To me it is not only possible, but *vital* to separate the issues

concerned. Yes, a battle for services is important but it is of equal

importance to see that autistic people of any and all ages are as

capable and as entitled to joy as anybody else. I don't see this event

as an attempt to sugarcoat anything or to misrepresent anyone. If it

was I would not want to be associated with it.

Recently in the US, the organization Autism Speaks released a short

film entitled 'Autism Every Day'. During the course of this film the

only side of autism that was presented was an unremittingly negative

one. Children were badgered into meltdowns and situations, by the

admission of the Director, were manipulated to show autism in the

worst possible light. One segment showed a mother telling how she

considered killing herself and her autistic daughter to escape the

misery of autism. She related this incident whilst her daughter was in

the room with her.

Consider the differences between this film and the Joy of Autism

event. The film was made for an organization called Autism Speaks -

the organization wishes to push themselves as the voice of autism,

that they are they authority on the subject. This event is organized

by an organization called The Autism Acceptance Project - referring to

a project to promote acceptance.

The film is entitled 'Autism Every Day'. The filmmakers wish to

present the idea that the unremittingly negative subject matter is the

sole reality of 'autism every day'. By contrast TAAP's Joy of Autism,

by its very title, indicates focusing on one aspect of autism. It

doesn't seek to eliminate the negative, merely to accentuate the

positive.

I can't see anything wrong with that aim. It puzzles me that anyone can.

-----

If I want a cure for anything, it would be for these divides: misery versus joy; normal versus abnormal; acceptance versus intolerance for autism itself.

Yet, there is a tie that binds all parents, those of us who want services, education, and opportunities for our children. There is little difference between the devotion many of us feel towards our children, the daily commitment toward them in ensuring their success.

The difference lies in our attitude towards our autistic children. Is success defined within the frame of “normal,” or is it defined individually, without preconceptions? The idea of normal baffles me. In trying to define normal, I only come up with more absurdities.

When we believe that something is extrinsic of us, then we can blame something outside of ourselves, our children. For some parents of autistic children, it might be easier, although there is no scientific evidence to prove this, to believe that autism is a mask that shields the true child within, or that autism is a disease akin to cancer, waiting for a cure. To acknowledge that autism is as much a part of the child as congenital blindness or deafness, may be akin to telling a parent that their autistic child is dead. To acknowledge autism as part of the child may seem hopeless, but this project is here to show others that it is not. The devastation a parent might feel in light of these ideas, that their child will “never” do something that was expected, can be crippling, and may even lead to hatred, some of which will be directed towards this project that wishes only to preserve the dignity and opportunity for not only our autistic children, but also for adults who are speaking up. These adults are saying “autism is part of who I am.”

As a parent who has gone through the very same experiences of other parents, who has seen the devastating messages and videos, I asked myself, “how is all of this going to help my son Adam or my family? How will this effect his self-esteem, and the challenges of being accepted into the mainstream community? Ralph Savarese, a professor from Grinnell College, who has written a memoir titled Reasonable People: A Memoir of Autism and Adoption, stated,

“As a father of an Autist, I can tell you that feeling good about oneself is a big problem with autism. What do you say to an eleven-year-old who so understands the world’s intolerance of difference when he starts announcing on his computer at night, `freak is ready for bed’? Like other people with disabilities, some with autism have found that identity politics offer a vehicle for fighting discrimination and improving self-esteem. It locates the problem with difference where it should be: outside the self, in a world of ignorance and fear.” (p.13)

In other words, placing judgment of others outside of ourselves, is an important way to preserve self-esteem. This is why The Joy of Autism event is hosting the work and presentations of autistic people.

Judgment was the first negative experience we faced when going through the diagnostic and early intervention process. There are people who judged Adam from the outset, peering at him as a pathology. They became more focused on what he couldn’t do rather than what he could do. I wouldn’t say those are good teachers. A good teacher is one who can see the child for who they are, to find a entry point, to teach where a child’s interest lies, to understand the challenges and address them without using them to define the child. One seasoned teacher told me last night, “I became a good teacher when I realized that the content of what I was teaching wasn’t important, it was the child who was important.” Read that sentence carefully and find the profound wisdom in it.

Michael Moon, who seems in many ways non autistic today on the exterior, claims that he was very challenged as a young autistic child, and continues to find challenges as an adult despite his higher functioning. As a teenager he suffered chronic fatigue syndrome from trying to “fit in,” not yet understanding that he was autistic. “When I found out I was autistic, it was a relief,” he said. “I knew I fit in somewhere.” He says that at the age of twenty, when he found out about his diagnosis, the world shifted, and he was more able to become part of it.

“School didn’t help me,” he said. “Schools were more interested in how you followed rules rather than teaching.”

Brian Henson, an Asperger’s adult from Brantford, Ontario also relays similar pain from his school years. “Teachers only wanted me to read the text book. I couldn’t ask questions. When I wanted to explore something, they told me to just read the text or I would get an F.”

“We’re only teaching your child how to respond,” said Jim Partington to me over the phone, a few days before I considered flying him to Toronto. Adam was only two years old. He was not relating to us well, and consistently ran back and forth. I thought, that teaching Adam to respond was not the means to an end. I wanted to teach him how to relate to me, and to be happy. We succeeded with lots of play. Adam is extremely intelligent, showing his knowledge in variant ways, one being the computer. He can do all of the skills suited to his age, and then some. He has more difficulty responding in a typical way. While we teach him now that he is older, happy and with respect for him (not using normalization of him as a goal – semantics are important here), I feel that we are building bridges between his world and ours.

When Adam was at camp, his head counselor asked his shadow, “what is it?” in terms of his limited speech, to which his shadow wisely replied, “he’s a child.” What difference would it have made for this young person to know that he was autistic? Would it have furthered her understanding of Adam as a whole child, or simply categorized him as an incapable one? I continue to ask the question: does the autism label help or hinder? If it serves to support autistic people and have them regarded as whole people as well, then I can support its use. If it is used to paint a horrific, disease-identity, where an autistic person is refused by teachers, therapists, and others, then it is wrong.

Paula Kluth, Ph.D., formerly from Syracuse University, and an expert in inclusive education and US legislation cites a quote by an autistic person:

“All my life I was enrolled in classes for the profoundly retarded. The pain of that isolation, I can’t describe. Some classes consisted of putting together flashlights together and then they would be taken apart for the next day’s project. I never spoke or made eye contact. I hummed and self-stimulated. No wonder they though I was hopeless. I was always treated well but my intellectual needs were never addressed because nobody knew I had any intellect at all. Sad to say, many like me remain in that same hellish situation.” (Kluth, You’re Going to Love this Kid: Teaching Students with Autism in the Classroom, p.23)

If there is any social injustice in the world that does a disservice to autistic children, it is those organizations and individuals who continue to paint autism as a horrible way of living and being. These are the same organizations that could help with what is: the reality that there are autistic people living in the world, who need education, and that there are families who need to feel inspired and empowered, not constantly pounded with the message that their child is insufficient. This is the disease mind-set that is negatively effecting so many people. If autistic people suffer, it is not from their autism. It is from society who judges them.

Jim Sinclair acknowledges the process of parental grief stating basically, that although it is understandable, it is not right to take one’s grief out on the child. He offers some advice, being an autistic person himself:

“After you’ve started letting go, come back and look at your autistic child again, and say to yourself: “This is not my child that I expected and planned for. This is an alien child who landed in my life by accident. I don’t know who this child is or what it will become. But I know it’s a child, stranded in an alien world, without parents of its own kind to care for it. It needs someone to care for it, to teach it, to interpret and to advocate for it. And because this alien child happened to drop into my life, that job is mine if I want it. If that prospect excites you, then come join us, in strength and determination, in hope and in joy. The adventure of a lifetime is ahead of you.” (from his essay, Don’t Mourn for Us)

I have to say that the turning point for me was when I began to read the books and essays written by autistic people and autistic artists who have found a language outside the written word: Lucy Blackthorn, Richard Attfield, Donna Williams, and so many others. Some of who can’t talk, and who have dealt with challenges, and society’s stigmatization of them for a lifetime. This stigma effects the entire disabled community, who despite their disability, want to be accepted and want the same things as you and I. The vast majority believe that disability means incapable. The idea that there is actually a sentient being behind the exterior of disability is intolerable to many, but precisely the opposite is true and must be dealt with head-on.

Over the past three years, and especially the past year, I have made an effort to travel to meet many autistic adults all over North America – some with “severe” autism, “Kanner’s Autism,” Asperger’s Syndrome. I have met adults who were mainstreamed into schools when schools didn’t know the word autism to the extent we do today. I have met others who were institutionalized in the 1950’s when it was considered shameful for families to have children with any disability. Some of these people, now adults in their late fifties and early sixties, said they were put on psychotic drugs and were treated poorly. One woman I met from just outside of Toronto was diagnosed with “Kanner’s Autism” has worked for thirty years since leaving a psychiatric hospital. As a child, she was placed in a facility for children with emotional disturbances. She managed to get married, drive, work and live her life as we all do.

Barbara Moran, from Topeka, Kansas (I am careful whose names I will use – I have received permission from some but not others as of yet), stated that she too was institutionalized. She says "just think of all children who were autistic placed in institutions back then, who we never hear from." Now in her fifties, she is extremely sensitive to noise and cannot work. She says she could have done better if she was accepted and allowed to go to regular school “where I could have been desensitized,” she notes. She says that the drugs she was placed on nullified her, and she hated being on them.

Larry Bissonnette, who uses a keyboard to communicate full sentences said to me “people who think your disability is an illness need to be cured of their ignorant attitudes.” Larry was also institutionalized until his sister saw how he was treated. She pulled him out and now lives with her, making art, traveling around the world on occasion. I met him and experienced his humour, his human-ness. Despite the challenges in communication, he is profoundly intelligent. It breaks my heart to receive emails from parents who cannot find the daily joy in their children, in these people who can teach us everything about autism.

Science has not yet provided any answers about autism, only more questions. Some science is unveiling the abilities innate to autism, thankfully, as it garners respect for a human condition, creating the needed bridge between so-called “different worlds,” to reveal that our worlds are not that far apart. As a parent who has sought answers from a variety of autistic adults, after hearing them tell me of their experiences, what worked for them and what didn’t, and the overriding message of each of them wanting to enjoy life, to be tolerated, understood and accepted by society, I had to ask myself what the point was in attempting to “normalize” Adam. For to do so would have meant that I did not value him as he was, or was unhappy with him.

No, autism is a challenge for the rest of us because we only see through one lens. We have to ask ourselves – is it the only lens? Is it the only way to look at autism? What of the autistic perspective? Is there a right way to be and a wrong way to be?

I’ve met parents who have revealed to me that “of all my children, my autistic child brings me the most joy.” This comes from two families I have encountered personally. Many others write about it: Paul Collins, Susan Senator, Valerie Paradiz, are some. It is something I strongly relate to, as Adam is my first and only child, my life, my reason for being, my utmost joy. Reframing my expectations of him has brought me daily surprises. I no longer expect myself in my pencil skirt and hat sitting at his Harvard graduation, but I also can’t say it won’t happen, or that I might not be sitting at his high-school graduation beaming at his success. As parents, we all know that the milestones our children do achieve give us monumental joy.

My husband likes to play devil’s advocate. I like that because I never think that there is one conclusion. Autism has revealed that to be human is living in paradox. He asks me, “So what if there was a pill to cure Adam? How are you gonna answer that?”

I can’t say that is an easy question to answer. Do I want Adam to suffer the stigmatization that a judgmental society will bring upon him? No, of course I don’t. I’m not sure if a pill could ever cure external judgment of him or of me for that matter.

Is autism curable? There isn’t one scientist that has proclaimed that it can be. In fact, the landscape of autism is so diverse, that one magic pill might not do the trick for everyone.

And if there was a pill? I just don’t know. To answer that question quickly is scarier than the question itself. Autistic people say that autism is a challenge, but still, they don’t want to be cured. Oliver Sacks once noted that we need to appreciate diversity in all its forms and called the brain “remarkable [in its] plasticity, its capacity for the most striking adaptations” as the “creative potential” of disease itself. People who have been medicated to the hilt, nullified of their experiences with neurobiological disorders, have suffered a marked decline of their creative abilities. I have to listen to this. We all do. If there was that pill, I would want Adam to decide, but even that answer is much too simple.

So do I deal with the reality of what is? Absolutely.

So now, I will reveal some of the responses, calling The Autism Acceptance Project “a political fringe,” to which I do not sigh, but perhaps acknowledge because eventually, a fringe becomes a mainstream. At least I hope that tolerance and acceptance will become mainstream. This project is about celebrating human dignity, potential and seeks to perpetuate respect so that we can ask for a variety of services and education to governments and teachers who just might see the individual potential of an autistic person. Waiting for a cure will not help us obtain services, support, vocational training. Governments will simply wait for those cures as a cost-saving measure.

Jonathan Lerman in Vestal, New York, is experiencing something akin to an team that enables his self-determination and empowerment, with support. It is a government-funded program. I cannot attest to how it is working, but the concept is interesting and might be considered. Jonathan basically states what he wants to do, and his team of people that support him, including his parents, ensure that his wishes and goals are realized. I believe that teenagers should continue to be supported with their peers, with self-image, that adults should receive vocational training, placement and support. I believe that inclusive education is a right, and that special education is also a right. Autistic people need access to a variety of approaches and educational opportunities. Above all, autistic people need self-determination.

How do the following statements encourage or hinder these needed services? To paint autism as a horrific disease waiting for a cure? Or an ability, a way of being, that deserves respect and opportunity to reach its potential? I am not revealing these responses out of disrespect for those who wrote them, or to create more divisions, but rather, as an opportunity for us to see the difference between empowerment/disempowerment in hopes that some may choose to find the same kind of joy and inspiration that my son has brought to our family.

Response #1:

I have to say; shocked is a mild word for my reaction.

As a parent of a child with autism, I applaud any effort to help the world understand this mysterious condition and the enormous strain it puts on those it afflicts and their families. However, to de-stigmatize autism with a sugar coating does this challenge a major disservice. Many of us actively advocate for those suffering with autism and accurate public education is critical. Making autism seem like “a happy place” doesn’t help our cause.

Response #2

While I am sure we all appreciate the benefits that accrue to children who are involved in artistic self-expression (and I am particularly sympathetic to this as a professional musician), this is an issue quite separate from the matter in hand - which is the choice of or tacit approval of the title "The Joy of Autism". This will not produce controversy, it will elicit fury. Parents who are trying to access funds and services, who are managing children with trying behaviours and who are fighting for educational equality do not want to have to deal with its implications.

What is next? Happy and Leukemic? Cancer is Cool? Incest is just another kind of love? I really hope you will not only appreciate the full horror of this gaffe, but do something public to acknowledge it! The good the event is certain to achieve will doubtless be diluted by the negative reaction from the autism community.

Response #3 (I apologize for the awkward spacing as this was taken from an email to me from Kevin Leitch of Autism Hub):

As parent to an autistic child considered to be 'classically' autistic

(other terminology includes low functioning/Kanners) one of the most

troubling aspects of the international autism community (by which I

mean the self appointed organizations of largely non-autistic people)

as oppose to the autistic community (by which I mean the organizations

comprised of a mixture of autistic and non-autistic people, or solely

autistic people) is the way in which a lot of people are opposed to

any attempt to present a non-tragic face to autism.

There is no denial that raising a child who has special needs is

difficult but it worries me that people want to compare an attempt to

look at a less negative aspect of autism to incest and cancer.

It seems to me that there is a large element of pre-judging occurring

here. Both in terms of what the event itself is and in terms of what

autism 'must be' for all people.

To me it is not only possible, but *vital* to separate the issues

concerned. Yes, a battle for services is important but it is of equal

importance to see that autistic people of any and all ages are as

capable and as entitled to joy as anybody else. I don't see this event

as an attempt to sugarcoat anything or to misrepresent anyone. If it

was I would not want to be associated with it.

Recently in the US, the organization Autism Speaks released a short

film entitled 'Autism Every Day'. During the course of this film the

only side of autism that was presented was an unremittingly negative

one. Children were badgered into meltdowns and situations, by the

admission of the Director, were manipulated to show autism in the

worst possible light. One segment showed a mother telling how she

considered killing herself and her autistic daughter to escape the

misery of autism. She related this incident whilst her daughter was in

the room with her.

Consider the differences between this film and the Joy of Autism

event. The film was made for an organization called Autism Speaks -

the organization wishes to push themselves as the voice of autism,

that they are they authority on the subject. This event is organized

by an organization called The Autism Acceptance Project - referring to

a project to promote acceptance.

The film is entitled 'Autism Every Day'. The filmmakers wish to

present the idea that the unremittingly negative subject matter is the

sole reality of 'autism every day'. By contrast TAAP's Joy of Autism,

by its very title, indicates focusing on one aspect of autism. It

doesn't seek to eliminate the negative, merely to accentuate the

positive.

I can't see anything wrong with that aim. It puzzles me that anyone can.

-----

If I want a cure for anything, it would be for these divides: misery versus joy; normal versus abnormal; acceptance versus intolerance for autism itself.

Tuesday, August 15, 2006

Thursday, August 10, 2006

Hope is Vested in Humanity

I've been looking for a photograph for the piece that will be published next year. It is a piece about Adam, autism, family life. I called it "The Perfect Child." I like this photograph. It was taken in the throes of worry, when Adam was newly diagnosed; when clinicians and psychologists consumed us in their leather couches, saying um hum, and scratching their pens against lined paper, peering at Adam from behind dark rimmed glasses. I remember feeling angry at them. How dare they view my first and only beautiful child as a pathology? I remember hiring and firing so many therapists and clinicians who came into our home -- our door might as well been revolving.

This photo brings me back to this time when I was worried, angry, confused. It reminds me of all the terrifying things I saw, the films of autistic people screaming, being tugged by therapists. Yes, there are many movies like those.

Soon, The Autism Acceptance Project will release its video. It was made to give people dignity, others hope. In a world where there is little, where people put all their stakes in cures, pills and perfection, we need to remind ourselves that in the end, hope is not vested in cures, it is vested in humanity.

Wednesday, August 02, 2006

Toddlers in Black

I picked up Adam at camp today when his head counselor announced, “Tomorrow is Olympic Day. The teddies [his group name] have to come wearing black.”

The mothers stood bewildered.

“Black? My child doesn’t own anything in black,” one said in disgust.

Another just rolled her eyes.

“Who makes these decisions?” asked another “Why don’t you know anything about children?” I don’t think anyone in the group owns a black anything. Not at this age.

Instead of colourful toddlers strolling about the camp tomorrow, they will be dressed in dark black under the sun. I can picture it now, a line up of toddlers marching to their event, these dark shadows, perhaps in black sunglasses -- a set of oblivious spy kids, cranky under the raging heat of the sun. It’s a rather morbid scene in my head. These red-faced and sweaty toddlers, following in a row like walking a funeral march. Not at all a sight I would expect, these bundles of joy who should be dressed in every colour of the rainbow, but not in black.

“Perhaps we can just cut out black circles and tape them to their backs,” suggested Adam’s shadow.

“Sure,” I said. “It’s better than dressing in black. Now they’ll all look like a bunch of walking targets.”

The mothers stood bewildered.

“Black? My child doesn’t own anything in black,” one said in disgust.

Another just rolled her eyes.

“Who makes these decisions?” asked another “Why don’t you know anything about children?” I don’t think anyone in the group owns a black anything. Not at this age.

Instead of colourful toddlers strolling about the camp tomorrow, they will be dressed in dark black under the sun. I can picture it now, a line up of toddlers marching to their event, these dark shadows, perhaps in black sunglasses -- a set of oblivious spy kids, cranky under the raging heat of the sun. It’s a rather morbid scene in my head. These red-faced and sweaty toddlers, following in a row like walking a funeral march. Not at all a sight I would expect, these bundles of joy who should be dressed in every colour of the rainbow, but not in black.

“Perhaps we can just cut out black circles and tape them to their backs,” suggested Adam’s shadow.

“Sure,” I said. “It’s better than dressing in black. Now they’ll all look like a bunch of walking targets.”